Fear & Loathing in Aztlán: Hunter S. Thompson and Oscar ‘Zeta’ Acosta’s Precarious Quest for Justice

Hunter S. Thompson & Oscar ‘Zeta’ Acosta. Sleeve Photo from “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

“California was not all about alternative states of mind but, more emphatically, about courageous political alternatives and attempts to redefine the social texture, about racial and class struggle.”

(Ilan Stevens, Foreword, Sal Si Puedes (Escape If You Can) Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution, by Peter Matthiessen)

Introduction

Palm trees, ocean surf and Hollywood glitz are what tends to come to mind when non-Californians think about California. There is also the common misconception that, at least since the gold-rush era, California was a vast, unpopulated frontier, there for the taking. The rise of the automobile and the implementation of trans-national highways abetted this belief, as the State was sold as an idyllic land of glimmering hope. Correspondingly, brash New Yorkers, dust-bowl Okies and returning GI’s all flocked to Southern California for their slice of the pie; of heaven on earth.

The reality, however, is that California’s shadowy side is more predominant; the part shrouded in dismal grey, wet, and prevalent fog. The land of massacred Indians, despised Spics, ghetto gang-bangers, and broken dreams; the California of Phillip Marlowe, Jake Gittes’ Chinatown, Crips & Bloods, Zoot Suiters, Vatos Locos and Charlie Manson; violent, oppressive, and wild. Oftentimes this fact is glossed over to sell the dream, which relies on human nature to overlook myriad problems to focus on the potential of being one of the few who make it to that Spanish-colonial mansion, or Malibu modern.

For most, though, the dream of owning that expansive beachfront property is something that fades with youth, as the day-to-day reality of mere survival takes precedence. There are also those Californians who see the decadent ways of the elite as the root of what ails the golden state, preferring to gravitate toward the counter-cultural milieu which has always been part of California’s conscience. This point of view has always been appealing to me, despite being raised in a prototypical, idyllic California beach town.

California’s shadowy side became prominent in the summer of ’76, as America was drenched in red, white, and blue bicentennial celebrations. Television, radio, and film prominently showcased this event, and even in my Middle School, the themes for dances or any sort of celebration resonated with it. By July 4th of that year, it had reached fever-pitch and Americana was pervasive. However, if one searched hard enough in newsprint, or were trapped in socioeconomically challenged communities, i.e., part of the “wrong” crowd, the reality of the failed, yet widely advertised American dream was evident.

That bi-centennial summer also stood out in that it provided me with the framework for navigating the anti-heroic landscape dominating my quaint So-Cal town in the form of two books; the first being Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter-Skelter, which didn’t shy away from the gory details of the Manson family murders, and recounts Bugliosi’s horrific journey in bringing them to justice. Helter Skelter was a wake-up call from the belief that the world was a safe, benign place where community would protect me from the harsh reality of the world outside my comfort zone. Manson was the ultimate boogeyman, taking the place of La Llorona in the dark recesses of my mind, and had me looking over my shoulder as I walked alone down the street.

Reinforcing this experience were the projects a couple blocks from my house: the rows of flimsy apartments behind the 7-11, which stood in stark contrast to the vast lemon groves and barrancas across the street, where droves of kids ran free. The barrio/projects were connected to the outside world via a breezeway which ran along the side of the 7-11 on one side, and an open irrigation ditch barricaded off with a chain-link fence on the other. Traversing its unlit length at night was a test of courage which provided ample opportunity for my imagination to conjure up grotesque visions while hurrying past the graffiti-laden wall. A sleep-over at the age of twelve at a friend’s house in these projects provided my first occasion for experiencing gunfire; shotgun blasts in the middle of the night from the vatos of La Colonia, who, unbeknownst to me at the time, were our mortal enemies. Their blasts were my baptism into a world surrounding me, yet up till then had always been something only spoken of in hushed tones; a rumor of sorts.

The second book of that bi-centennial summer was Hunter S, Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, recommended by an uncle who was into his own drug-fueled escapist journey à la Thompson and his Attorney, “Dr. Gonzo,” in their search for meaning in the patriotic fervor of the times. Thompson’s biting, satirical humor was the hook which drew me into his tale, seeming particularly relevant due to my direct experience with the dark side of society, and the already doomed quest for social justice evident in the strikes of the United Farm Workers (to which my grandparents, as life-long immigrant pickers belonged to and were active in), as well as the legal battle for Native America playing out via the Leonard Peltier case and the American Indian Movement; not to mention the legal struggles of my extended family as witnessed personally in the court rooms of my hometown. Given these circumstances, the rampant patriotism of the time and its idyllic promise of a pax americana couldn’t hold a candle to my personal experience, and the dark, murderous tone of the day.

However, the most often overlooked, yet most relevant fact regarding Fear and Loathing is that it was delivered under the veneer of the roman á clef; its protagonists given pseudonyms to protect their identities; “Dr. Gonzo,” Thompson’s “300-pound Samoan Attorney,” being the Chicano Activist, Lawyer, Writer, and general enigma, Oscar ‘Zeta’ Acosta, and “Raoul Duke” as Thompson.

Indeed, the device of the roman á clef is part of the history of Thompson and Acosta’s relationship, and while both men chronicled one another, their respective stories offered divergent records of their history, commencing with their initial meeting. In his Rolling Stone piece Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, (Rolling Stone #81, April 29th, 1971) Thompson recounts that he first met Oscar Acosta in Aspen, Colorado in 1967 at a bar called “The Daisy Duck,” where purportedly, Acosta had aggressively approached him, going on about “ripping the system apart like a pile of cheap hay, or something like that,” prompting Thompson to think to himself, “Well, here’s another one of those fucked-up, guilt-crazed dropout lawyers from San Francisco – some dingbat who ate one too many tacos and decided he was really Emiliano Zapata.”

Conversely, in his Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, Acosta recounts the same meeting from a different perspective, giving Thompson the pseudonym of “King,” and referring to Aspen as “Alpine”, he recounts Thompson was introduced to him as a published writer (for his recent Hell’s Angels book), with shared acquaintances reaching back to Acosta’s crew at his local watering-hole back in San Francisco; in a time when the national web of drunks at dive bars provided fertile ground for tall tales, bizarre characters, and unlawful acts which created colorful desperadoes; a self-enclosed world where the ultimate cachet was in one’s ability to be an extremely entertaining counter-cultural alcoholic; an environment where the name-dropping isn’t about how famous one’s friends are, but how infamous they might be.

Although Thompson is somewhat critical of Acosta in the beginning, Acosta returns the favor when writing about that first, fated meeting between them at the Daisy Duck in Alpine, writing:

“The other one was tall and on the verge of losing his hair. He wore short pants, an upside-down sailor’s cap from L.L. Bean and a holstered knife hung from his waist. He looked the other way when Bobbi introduced me to Miller and told him I’d been in Ketchum.

“This is King,” Miller said. He is a friend of Turk’s.”

Christ, I thought, another biker from Chicago! He turned, gave me a quick once-over and said, “You from San Francisco, too?”

“Nah, I’m from Riverbank.”

“King was driving the bike when Tibeau broke his leg.”

And so, when he showed me an autographed copy of King’s book and asked me to buy him a beer while I thumbed through it, the devil was setting me up for this confrontation with the tall, baldheaded hillbilly from Tennessee.

(Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, p.137)

The racist banter between Thompson and Acosta at the outset of their acquaintance would be a persistent undertone throughout the course of their relationship. Acosta is aware of it, and accordingly records it for posterity, noting there are specific times and places for it. Also, in these moments, one must agree to let one’s guard down and not be offended, i.e., there must be a modicum of respect there initially to open the door to it. Acosta describes this mindset somewhat in the 70’s Chicano Journal, Con Safos, writing:

“It is this anarchy of socialization, this willingness to strike at all self-image masking as reality that permitted me the freedom to open my sores before these strangers. It is not that I had never been beaten over the head by others; for insult couched in smart-talk was the permanent style of conversation at the bars I had frequented for years in San Francisco.”

(Con Safos Magazine, Volume 2, Winter, 1971)

Without a doubt, this sort of interaction was commonplace at the time. Acosta experienced it from the constant jabbing with Okies in his hometown as a teenager, and later with the wise-cracking jazz musicians he played with in the “Fighting 573rd” Air Force band he was part of while stationed in Panama between ‘54 and ’56. However, referring to the jousting at the Daisy Duck, he says this:

“There was, however, a substantive difference between the jazzmen of the fifties, the artists and beats I knew in San Francisco as contrasted with the freaks I crashed into in Aspen at the Daisy Duck. These latter would not wait until they knew you before they attacked your gods; introductions were intentionally omitted and descriptions of status were strictly forbidden. The assignment of value to an act or condition of one’s self by one’s self simply prompted a negative response; familiary and/or friendship played no role whatsoever in the dialogue of freaks. The attack against irrelevancies was aimed at friend and foe alike. They slaughtered man, woman and child without regard to race, color, or creed, these new barbarians.”

(ibid. p. 38)

When reflecting on those initial meetings between the two; Thompson’s referring to Acosta as “some dingbat who ate one too many tacos and decided he was really Emiliano Zapata,” and Acosta’s countering with “the tall, baldheaded hillbilly from Tennessee,” we become privy to the general tone of the no-rules, lawless, and dismissive nature of back-country, homogeneous places such as Aspen. Back then, (as well as now), deep-seeded racism is part of a national fabric which allows sarcasm as a viable means of communicating in the spirit of being “hip” enough to be conversing and spending social time with someone from whom your cultural group despises, even if these interactions have a decided edge to them. In addition to this, the hard-drinking bar circuit, while being a venue for accepted madness, was also a place where it was understood that everything said by and about someone was to be taken with a grain of salt. The opportunity to be hoodwinked or ripped-off always at the forefront.

However, despite the racism and the suspicion, somehow, the day after their initial meeting, Acosta groggily comes to in Thompson’s basement, unsure of where he was, or how he got there. The first thing Thompson guardedly tells him is, “Let me warn you right now…I don’t want any trouble out here. I only let you stay last night ‘cause we couldn’t move you.” Acosta, though, is equally unsure of Thompson, due to the amazing array of weapons displayed throughout the house, countering Thompson’s harsh tone with, “You’ll get no trouble from me… as long as you don’t shoot me with those fucking weapons.” This sort of stand-off would prove to be an element of their multi-year friendship, counter-balanced by their curiosity of one another, played out in an ongoing chess-match of wits; a game willfully engaged in as either proved to be exceptions to what they expected from others of their kind. This much was evident from that initial meeting, as Thompson replies to Acosta’s previous statement by replying, “I’ve heard that one before,” he nodded, gritting his cooked teeth,” to which Acosta replies, “Not from me you haven’t…I’m not like the others.”

“Yeh, sure…you’re an Aztec lawyer. I heard all about it.”

(Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, p.170)

While the racial element played out between the two, the deeper bond of free-spiritedness and counter cultural impulses, fed by a voracious appetite of booze and a variety of pharmaceuticals provided the groundwork for their burgeoning relationship. It is within these boundaries where their mutual trust of one another flourished, the seed of their friendship took bloom. There are a variety of ways this bond might be analyzed from a psychological perspective, and, in Acosta’s case, psychoanalysis factored prominently into his life before he decided to ditch it for the freewheeling bacchanalia he would embark upon before and after he met Thompson. Acosta felt the answers analysis provided to his psychoses too confining and cerebral: he wanted to experience the root of it all, get so close to the flame he might get some minor burns before he could understand and perhaps acquiesce to it. By the time he crosses paths with Thompson in ’67, he already frequently engages in drugs, their influence fueling his going afoul of the law and influencing his decision-making. However, in Thompson, he found a kindred spirit equally disdainful about current affairs, all too willing to alter one’s mind to better cope with reality.

To that point, the morning after he wakes up in Thompson’s house, the two sit out on the patio and begin a bout of day-drinking, the fact the local Sheriff is looking for Acosta hanging over their heads:

“He gave a wicked smile with those thin lips that barely moved when he talked. He left me alone with the Dobermans. I saw him through the front window at the record player. “Mr. Tambourine Man” by the kid seemed to fit just right as I leaned back and soaked up the sun with my fourth can of Budweiser in less than an hour. Would they get me? I swallowed my last three bennies, the big white fuckers with a cross. Fifteen mgs. of amphetamine moves you just about right when you’ve got a hangover and the Sheriff’s looking for you. If you’re used to them, of course.”

(ibid. p.171)

A few days after that, they’ve already fallen into a pattern which invariably would be immortalized in Fear and Loathing; one which finds them imposing their drug-fueled will on those around them; refusing to play by the rules and acting out their inner-demons in Falstaff-like fashion, impervious of the consequences. Knowing Acosta is being tracked by the Sheriff, they don masks in a comical attempt to disguise themselves and load up on booze and drugs, then head out on the town to see what they can stir up. This leads to an incident that portends a fateful event in their future involving tear gas and a bar, and it had one wondering whether, or not karma might have played a role in those circumstances. Acosta tells the tale in his Autobiography:

“We don’t have time for that now…open that envelope Scott left you. We’re going to need some good mescalin now.” We sucked on Scott’s powder until our faces turned blue, then sped over with our weapons to the Daisy Duck and demanded free drinks from Phil.

“So what’s this, Tonto and the Lone ranger?” He asked. We’d decided to put the masks back on until dark in case Whitmire came looking for us.

“Don’t mess with us, boy!” I warned him. The lights were fading fast for me. The oil paintings of zoftig nudes in the bar were staring right at me.

“Just get us whiskey…and put it on my tab.” King demanded. Perhaps if Phil had moved faster King wouldn’t have set it off, but it had been a wild weekend and Phil wasn’t quite the pussy his pudgy lips indicated. When the bomb went off there were only two others in the bar: tourist-looking types, fun hogs with burly muscles and crew cuts trying to act cosmopolitan in neatly pressed dress pants. They yelled as if they had been hit and ran out screaming “Goddamn hippies!” The tear gas spread quickly and evenly before Phil could reach us with his cue stick. King and I ran out the back, jumped over the railing of the sun deck and got into the car. We saw the red light of the sheriff’s blue Mustang as we pulled away.

“There’s no hope for you now,” he said as we sped down the highway out of town leading to Snow Mass.

“There’s never any hope for poor Aztec lawyers,” I mumbled.

“Don’t get carried away with yourself. Just keep your eyes open.”

“What for? It feels better closed.”

(ibid. p.178)

Thompson telling Acosta, “Don’t get carried away with yourself,” speaks to the way he viewed self-introspection, his modus operandi being one of staying aware and alive in each passing moment; sucking the marrow out of the bones of life in a heightened state enhanced by drugs. In this space, there is no time for reflection, self-pity, or doubts. There is only the “now,” and the will to get on to what’s next; a marauding, conquest-filled point of view which seeks to enrich the individual and provide fodder for the imagination which might provide substance for one’s art. While Acosta was initially similarly inclined, as time went on, and he became more entrenched in the Chicano movement, particularly in his role as a lawyer and leader, his focus had to shift away from this point of view by necessity, as his affiliation with the movement focused more on the collective, rather than the individual.

Invariably, the struggle for identity became all-consuming for Acosta, as the reality of being a self-professed “Chicano” comes with the unique predicament of not belonging to one group or the other; disdained and misunderstood by Mexican nationals for not being one of them, and equally despised by Americans for belonging to the “other,” one is only seen as “pocho” or “spic”: i.e., ignorant of Mexican culture, or unwelcome in their country of origin. Thompson had no such personal struggle. His counter-cultural efforts were more directed at the fight for the soul of America as a democratic concept and the legacy of Colonial America via its westward expansion: more about the responsibility that came with the promise of such documents as the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Acosta was focused on the failure of those ideas and the liberation of the conquered lands his people had lost; the return of the homeland, of Aztlán.

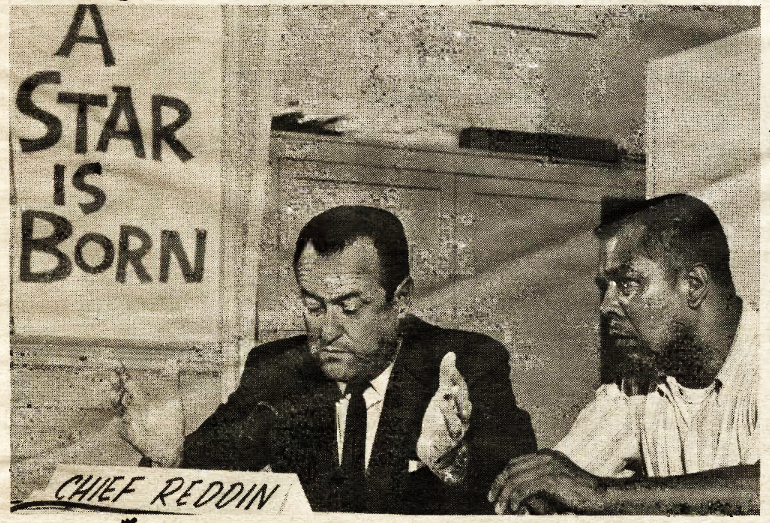

Eventually these differences would divide the two further. As Acosta went all-in on the concept of Aztlán, he lost ideological compatibility with Thompson, as well as with others who were focused on rectifying the American experiment. However, this was not the only thing which created a rift between the two. According to Abby Aguirre, who writes in her July 13, 2021 New Yorker piece, ‘What “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” Owes to Oscar Acosta’, the divide really came to the fore when the book’s publisher, Random House, sent a copy to Acosta for his review; their lawyers concerned about the record of his engagement in illegal acts compelling him to sue Random House for libel. However, as Aguirre writes, “when Acosta received the manuscript, he was incensed—not about the accounts of drug use or criminal behavior but because Thompson had transformed him into a “300-pound Samoan.” According to Aguirre (and many others), Acosta, “more than anything, wanted his ethnicity recorded correctly, as well as having his name and photograph displayed on the book’s dust jacket.” Apparently, Thompson informs him it was too late to change the text, “but he and Random House agreed to the latter request: the book went to press with a black-and-white photo on the back cover of Acosta and Thompson sitting in the bar at Caesars Palace, in front of two empty shot glasses and a saltshaker.”

In his defense, Thompson purportedly states, “My only reason for describing him in the book as a 300-pound Samoan instead of a 250-pound Chicano lawyer was to protect him from the wrath of the L.A. cops and the whole California legal establishment he was constantly at war with.”

Aguirre writes that Acosta would counter that:

“Much of the dialogue in “Fear and Loathing” was reproduced verbatim from tape recordings that Thompson had made of his conversations with Acosta; as an actor-participant in Thompson’s gonzo experiment, Acosta felt he had shaped the book in substantive ways. He believed that Thompson had helped himself to Acosta’s sensibility and personality—and then erased his identity. “My God! Hunter has stolen my soul!” he told Alan Rinzler, the head of Straight Arrow Books, a division of Rolling Stone. “He has taken my best lines and has used me. He has wrung me dry for material.”

While the perceived slight and betrayal may have seriously offended Acosta, it did provide him the opportunity to get a book deal of his own — something he had longed for since a young man; what he studied and worked at before getting discouraged and attending law school as a fallback. According to Aguirre, Alan Rinzler told her, “I did not have the idea to publish his autobiography because I was trying to mollify Oscar or get rid of him in some way, I did it because I thought he was a good writer. He had a voice.”

And what a voice it is. His two published works, Autobiography of A Brown Buffalo and Revolt of the Cockroach People are unique accounts of a time when the national fabric was stretched to its limits. And, while Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo starts out as a Bukowski-like account of the inner-workings of the down-and-out alcoholic, post-WWII; replete with plenty of misplaced machismo, feminine objectification, and homophobia, it winds up in a place that serves as a useful account of the early Chicano movement. By the time he opens Revolt of the Cockroach People, one is afforded a first-person report of the front-lines in the oftentimes bloody battle of said movement. Initially, his friend Thompson is there with him, writing about it, most often for Rolling Stone, but, as previously alluded to, the times caught either of them up on different waves, casting them in separate directions. Initially allied in their precarious quest for justice, the byzantine machinations of national and local policing and politics would chew them up and spit them out as the experimental sixties gave way to the sobering seventies. This is a theme in Fear and Loathing, but is only conveyed through Thompson’s comedic and sensational account. The more tragic and awful story lie on Acosta’s upcoming path; a place where the Helter-Skelter, Manson-like world would intersect with his in a paranoid, tragic, and fateful way. But before Acosta embroils himself in this scenario, back in the world of Fear and Loathing the writing is already on the wall concerning their impending ideological shift, Thompson writing early on in the book:

“You Samoans (read Chicanos) are all the same,” I told him. “You have no faith in the essential decency of the white man’s culture. Jesus, just one hour ago we were sitting over there in that stinking baiginio, stone broke and paralyzed for the weekend, when a call comes through from some total stranger in New York, telling me to go to Las Vegas and expenses be damned — and then he sends me over to some office in Beverly Hills where another total stranger gives me $300 raw cash for no reason at all… I tell you, my man, this is the American Dream in action! We’d be fools not to ride this strange torpedo all the way to the end,”

(Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, p.11)

What the pair blissfully ignore is that all this good fortune, obtained by chicanery, is at the expense of the rank and file; “the doomed,” as Thompson frequently refers to them, forgetting the dictum, “You don’t get something for nothing.” Acosta deep-down knows this, yet allows himself to go for the ride as means to compensate for the world’s transgressions. Thompson, on the other hand, sees this world of chance as a by-product of the American system; one of winners and losers. Of course, he’s not wrong, but it’s in how one wins or loses and what winning and losing truly means where he muddles it. For, oftentimes, winning is losing, and vice versa.

The Dreamers and the Vatos Locos: Dividing and Conquering a Movement

March for National Chicano Moratorium. Courtesy Security Pacific National Bank Collection

“They go back and re-create situations. Whereas, I’m either too lazy, or incompetent, or something. I…I only get into a story when I’m right there, which makes for a problem sometimes.”

(Hunter S. Thompson on the difference between his “Gonzo” journalism, and Tom Wolfe’s “New Journalism.” Excerpt from Hunter S. Thompson interview with Harrison Salisbury. UGA Brown Media Archives, April 16, 1975.)

Much like the jumbled record of the Seventies, the literary path of Thompson and Acosta is difficult to discern from the outside. One must do their homework and be prepared to follow the proper clues to understand the chronology of their journey. Doing so will reveal that Fear and Loathing was born from Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, (Rolling Stone #81, April 29th, 1971). However, one could only discern this by reading “Jacket Copy for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream” in Thompson’s 1979 book The Great Shark Hunt, where he conveys that while in the process of writing Strange Rumblings he is often beset with paranoia and a sense of dread:

“After a week or so on the story I was a ball of nerves & sleepless paranoia (figuring that I might be next) …and I needed some excuse to get away from the angry vortex of that story & try to make sense of it without people shaking butcher knives in my face all the time.

My main contact on that story was the infamous Chicano lawyer Oscar Acosta — an old friend, who was under bad pressure at the time, from his super-militant constituents, for even talking to a gringo/gabacho journalist. The pressure was so heavy, in fact, that I found it impossible to talk to Oscar alone. We were always in the midst of a crowd of heavy street-fighters who didn’t mind letting me know that they didn’t need much of an excuse to chop me into hamburger.

This is no way to work on a very volatile & very complex story. So one afternoon I got Oscar in my rented car and drove him over to the Beverly Hills Hotel — away from his bodyguards, etc. — and told him I was getting a bit wiggy from the pressure; it was like being on stage all the time, or maybe in the midst of a prison riot. He agreed, but the nature of his position as “leader of the militants” made it impossible for him to be openly friendly with a gabacho.

I understood this…and just about then, I remembered that another old friend, now working for Sports Illustrated, had asked me if I felt like going out to Vegas for the weekend, at their expense, and writing a few words about a motorcycle race. This seemed like a good excuse to get out of LA for a few days, and if I took Oscar along it would give us time to talk and sort out the evil realities of the Salazar/Murder story.

It had worked out nicely, in terms of the Salazar piece — plenty of hard straight talk about who was lying and who wasn’t, and Oscar had finally relaxed enough to talk to me straight. Flashing across the desert at 110 in a big red convertible with the top down, there is not much danger of being bugged or overheard.”

(The Great Shark Hunt, pgs. 105-11, reprinted in 1996 Modern Library (New York) Edition of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and other American Stories as Jacket Copy for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. pgs. 207-15)

Thompson’s candor regarding his feelings surrounding his old friend Acosta’s new inner-circle further explains the ideological schism the two would face as time marched on. His account also helps further explain the mindset behind his diatribe on the “American Dream” he conveys to Acosta in Fear and Loathing. It also speaks to the paranoia and racism inherent in the budding Chicano movement; sometimes warranted, at others, not.

Whether or not Thompson fully sympathized with and believed in the Chicano plight, his first-hand reporting of the incendiary events in East Los Angeles in Strange Rumblings are a vital record of the era. Perhaps the most important is his description of the rise of what he refers to as the “batos locos,” the young, disenfranchised youth of the area who seem bent on violent aggression as means for confronting the rampant political violence at hand in their communities.

“There are a lot of ex-cons in the movement now, along with a whole new element ̶ the “Batos Locos.” And the only difference, really, is that the ex-cons are old enough to have done time for the same things the batos locos haven’t been arrested for, yet. Another difference is that the ex-cons are old enough to frequent the action bars along Whittier, while most of the batos locos are still teenagers. They drink heavily, but not in the Boulevard or the Silver Dollar. On Friday night you will find them sharing quarts of sweet Key Largo in the darkness of some playground in the housing project. And along with the wine, they eat Seconal ̶ which is massively available in the Barrio, and also cheap: a buck or so for a rack of five reds, enough to fuck anybody up. Seconal is one of the few drugs on the market (legal or otherwise) that is flat guaranteed to turn you mean. Especially with wine on the side and a few “whites,” bennies, for a chaser. This is the kind of diet that makes a man want to go out and stomp people…the only other people I’ve ever seen heavily into the red/white/wine diet were the Hell’s Angels.”

(Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, p.230)

In Thompson’s description of the rise of the batos locos, we find the recipe for the current malaise facing not just the barrios of Los Angeles, but all slums and barrios in America’s urban centers: the combination of readily-available drugs and alcohol coupled with a sense of hopelessness among violent and depraved circumstances. In this matrix, the seeds of violence, hate and despair are sown and eventually bloom in the form of death and incarceration: both big business in the slums of America. Concerted efforts on the part of the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department exacerbated an already hostile situation, and while we make no excuses for the troubled youth of the time and place, we feel compelled to speak to the innocent and hard-working caught-up in the fray. While previous generations may have practiced turning the other cheek in an effort just to get on with their lives, by the end of the sixties and beginning of the 70’s, it became painfully evident this tactic was no longer prudent for the majority. While violent anarchy may not have been a proper response, organizing and educating the public on the dangers of day-to-day life in the barrios was a good place to start. Such efforts oftentimes took the form of massive public protests, strikes, and community events geared more towards celebrations of common goals.

To wit, a peaceful Anti-Vietnam demonstration, organized by a group referred to as “The Chicano Moratorium” was held August 29th, 1971 at Laguna Park (now Ruben Salazar Park), where about 5,000 peaceful liberal/student/activist groups and locals gathered to protest the drafting of young Chicanos to fight in the Vietnam war. According to Thompson’s Strange Rumblings article, as well as public record, “The police suddenly appeared in Laguna Park, with no warning, and “dispersed the crowd” with a blanket of tear gas, followed up by a Chicago style mop-up with billyclubs. In the aftermath of the violence, a Watts-style riot erupted and spread to Whittier Boulevard wherein three people were killed, sixty injured as well as damages to property estimated at about a million dollars. But of course, the big story that day was the death of Ruben Salazar. At that point, Salazar was a nationally-known veteran War correspondent, L.A. Times columnist, and had recently signed on as News Director for KMEX-TV.

Ruben Salazar

According to Thompson, Salazar had recently raised the ire of the L.A. County Sheriffs in a series of exposés, among them the story of a kid simply referred to as ‘Ramirez,’ who had died in their custody, prompting Salazar to infer he had been beaten to death. Accordingly, Thompson notes in the summer of 1970 Salazar had been “Warned three times, by the cops, to “tone down his coverage.” And each time he told them to fuck off.”

This heightened sense of combativeness between Salazar and L.A. County Sheriffs served as backdrop to the protest/rally that fateful summer’s day at the end of August 1971, of which Thompson writes, “the rally was peaceful all the way to the end, but then, when fighting broke out between a handful of Chicanos and jittery cops, nearly a thousand young batos locos reacted by making a frontal assault on the cop headquarters with rocks, bottles, clubs, bricks and everything else they could find.” The ensuing melee would lead to the circumstances which set the stage for Salazar’s death.

Sheriff’s begin to cordon off the Silver Dollar on Moratorium Day

Salazar had been covering the demonstration with Guillermo Restrepo - a native Columbian reporter and newscaster for KMEX-TV, with two of Restrepo’s friends acting as spotters and bodyguards, Gustavo Garcia and Hector Fabio Franco. Apparently, the group left the park after the scene turned violent and headed to the Silver Dollar Café “to take a leak and drink a quick beer before we went back to the station to put the story together.” However, unbeknownst to them, and all the bar’s occupants, at least a dozen deputies from the elite Special Enforcement Bureau (a sort of SWAT team) were responding to an “anonymous report” that a man with a gun was holed up inside the bar. Shortly after their arrival, the deputies purportedly issue a warning via bullhorn, ordering the occupants to “come out with their hands up.” Recognizing there was some sort of commotion outside, Gustavo Garcia steps out to see what was going on, and is promptly told by the assembled Sheriffs “To get back inside the bar if he didn’t want to be shot.” Garcia goes back inside and promptly warns Salazar there were cops outside about to shoot, to which Salazar purportedly replies, “That’s impossible; we’re not doing anything.” Several seconds later, without warning, the Sheriffs fired two high powered teargas projectiles generally used for barricaded criminals, and capable of piercing a one-inch pine board at 300 feet, through the open front door of the bar, one of which strikes Salazar in his left temple, blowing his head off. Meanwhile, an unknown man carrying an automatic pistol flees out the back door of the bar, and is confronted by the Sheriffs, who take his gun and astonishingly tell him simply to, “beat it.” Two more tear gas bombs are fired through the front door and then the bar is promptly sealed, without the Sheriffs ever entering. It remains sealed for a couple hours until they purportedly receive another “anonymous” report that there might be an injured man inside. The police then break down the door and find Salazar’s dead body.

In the wake of Salazar’s death, despite multiple eyewitness accounts which contradicted the Sheriff’s version of the incident, L.A. County Sheriffs stick with their story that they had come to the Silver Dollar to arrest the ‘man with a gun.’ However, as Thompson notes, eight days after Salazar’s death, the Sheriffs had yet to locate the source of the tip. A couple weeks later, at the coroner’s inquest the Sheriff’s office introduces a key witness who purportedly called the tip in, a local named Manuel Lopez, who claimed to have done many heroic deeds that day, among them calling the tip in. However, he is unknown to the many newsmen, investigators and other tipsters and eye-witnesses. All local news outlets rally behind Salazar, with the Los Angeles Times giving the most thorough account. Yet, despite their concerted effort, the inquest ends with a split verdict. Thompson quotes the L.A. Times’ Dave Smith’s piece of October 6th, which read:

“Monday the inquest into the death of newsman Ruben Salazar ended. The 16-day inquiry, by far the longest and costliest such affair in county history, concluded with a verdict that confuses many, satisfies few and means little. The coroner’s jury came up with two verdicts: death was ‘at the hands of another person’ (four jurors) and death was by ‘accident’ (three jurors). Thus, inquests might appear to be a waste of time.”

(Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, pgs. 248-49)

The Silver Dollar on Moratorium Day

Shortly thereafter, District Attorney Evelle Younger announces that “no criminal charge is justified” against Tom Wilson, the Sheriff who admitted to firing the shot which killed Salazar, and that was pretty much the end of it. Of course, the Chicano community was incensed, but most never really held much hope that justice would be served. Why would the tide suddenly change? In the aftermath of the inquest and all the indignant media coverage, Thompson summarizes the Sheriff’s view of the Salazar incident thusly:

“Salazar was killed, they say, because he happened to be in a bar where police thought there was also a “man with a gun.” They gave him a chance, they say, by means of a bullhorn warning…and when he didn’t come out with his hands up, they had no choice but to fire a tear gas bazooka into the bar…and his head got in the way. Tough luck. But what was he doing in that place anyway? Lounging around a noisy Chicano bar in the middle of a communist riot? What the cops are saying is that Salazar got what he deserved —for a lot of reasons, but mainly because he happened to be in their way when they had to do their duty. His death was unfortunate, but if they had to do it all over again they wouldn’t change a note.

This is the point they want to make. It is a local variation on the standard Mitchell-Agnew theme: Don’t fuck around, boy—and if you want to hang around with people who do, don’t be surprised when the bill comes due—whistling in through the curtains of some darkened barroom on a sunny afternoon when the cops decide to make an example of somebody.”

(Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, pgs. 250-251)

Aside from the tragic circumstances surrounding Ruben Salazar’s death, an even greater tragedy was committed in the beginnings of the splintering of a united Chicano movement by introducing violent circumstances to non-violent causes. The university students, community organizers and working-class people appealing to the institutional apparatus expected a non-violent response which followed the democratic principles they themselves adhered to. However, America was by no means prepared, or willing to accept the sweeping changes sought in the 60’s and 70’s. Deep-seeded, institutionalized racism (which still exists today, and one might argue in even more vehement terms) was too ingrained into the machinations of government and civics. The primary tactic of introducing violent circumstances to non-violent movements was a proven way of instigating a violent response which would be used as reasoning that respective movements were “dangerous.” There is no doubt the “batos locos” and like-minded minority groups were problematic in their violence, however, one could argue they were no more dangerous than Anglo biker clubs such as the Hell’s Angels, who, at the time were at least equally as dangerous, and remain so today.

In the spirit of his developing “Gonzo” style of journalism, Thompson is forthcoming about his personal interest in the Ruben Salazar story, writing that it was in Salazar’s capacity as a reporter who was threatening to uncover the illegal and immoral acts of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department which drew him to the story:

“The Salazar case had a very special hook in it: Not that he was a Mexican or a Chicano, and not even Acosta’s angry insistence that the cops had killed him in cold blood and that nobody was going to do anything about it. These were all proper ingredients for an outrage, but from my own point of view the most ominous aspect of Oscar’s story was his charge that the police had deliberately gone out on the streets and killed a reporter who’d been giving them trouble. If this was true, it meant the ante was upped drastically. When the cops declare open season on journalists, when they feel free to declare any scene of “unlawful protest” a free fire zone, that will be a very ugly day ̶ and not just for journalists.”

(Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, p. 228)

Thompson’s interest in Ruben Salazar’s story is merely part of his writing process; a component of his emerging gonzo style of journalism, which places him squarely in the middle of the story, where he might get caught up in the immediacy of the moment. Admittedly, Thompson is no supporter of the conservative powers in control of America at the time. Yet he also is no champion of any cause other than his own, as told from the perspective of the occupation of the journalist:

“When the cops declare open season on journalists, when they feel free to declare any scene of “unlawful protest” a free fire zone, that will be a very ugly day—and not just for journalists.”

When Thompson does discuss the Mexican-American situation at the time, it’s clear he is primarily quoting Acosta and his perspective:

“Ruben Salazar is a bonafide martyr now ̶ not only in East L.A., but in Denver and Santa Fe and San Antonio, throughout the Southwest. The length and breadth of Aztlan ̶ the “conquered territories” that came under the yoke of Gringo occupation troops more than 100 years ago, when “vendido politicians in Mexico City sold out to the US” in order to call off the invasion that gringo history books refer to as the “Mexican-American War.” (Davy Crockett, Remember the Alamo, etc.)

As a result of this war, the US government was ceded about half of what was then the Mexican nation. This territory was eventually broken up into what is now the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and the Southern half of California. This is Aztlan, more a concept than a real definition.”

(Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, p. 229)

Thompson must also rely on Acosta to detail the growing divide within the Mexican-American community at a crucial period, as he is oftentimes perceived as an outsider; a gabacho, i.e., an untrustworthy Anglo. In any event, he does faithfully convey the growing divide as described him by Acosta regarding the growing influence of the “Aztlan” concept and how the community should deal with growing police presence in their neighborhoods:

“But even as a concept it has galvanized a whole generation of young Chicanos to a style of political action that literally terrifies their Mexican-American parents. Between 1968 and 1970 the “Mexican-American Movement” went through some drastic changes and heavy trauma that had earlier afflicted the “Negro Civil Rights Movement” in the early Sixties. The split was mainly among generational lines, and the first “young radicals” were overwhelmingly the sons and daughters of middle-class Mexican-Americans who had learned to live with “their problem.”

At this stage, the Movement was basically intellectual. The word “Chicano” was forged as a necessary identity for the people of Aztlan—neither Mexicans nor Americans, but a conquered Indian/Mestizo nation sold out like slaves by its leaders and treated like indentured servants by its conquerers. Not even their language was definable, much less their identity.

(Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, p. 229-30)

With minority groups, the plan is always to divide and splinter, concentrate on the violent aspects of it, sensationalize them in the media, and in the process create fear in outside communities. Days such as August 29, 1971 provided the perfect opportunity for this macabre end: a large, agitated crowd, a harsh police presence, and a well-thought-out exit strategy which would use governmental processes to exonerate the perpetrators. This is the recipe which has stood the test of time. Witnesses such as Thompson and Acosta can only watch the process unfold and tell their side. However, their voice only conveys so much weight at the end of the day, when legal institutions trump any other factor in who gets what, where, and when.

In time, Thompson’s popularity as a writer becomes an entity unto itself, as he takes on the persona of Dr. Thompson, and Acosta gradually succumbs to the violent machinations of a losing battle for Chicano rights. This fact would lead to his eventual demise, a conclusion he never seemed to shy away from, and one which provided Thompson with the distinct core of his inimitable style.

Of Brown Berets & Buffaloes

Gloria Arellanes’ Brown Beret. Courtesy Cal State LA Archives.

“They moved north, and there Aztlán was a woman fringed with snow and ice; they moved west, and there she was a mermaid singing by the sea…They walked back to the land where the sun rises, and…they found new signs, and the signs pointed them back to the center, back to Aztlán.”

(Rudolfo Anaya, Heart of Aztlán. University of New Mexico Press, 1976.)

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and Oscar “Zeta” Acosta had similar upbringings, both on a trajectory that would inevitably intersect in a historical and profound fashion. Both their fathers were from Mexico; Gonzales’ from Chihuahua, Acosta’s from Durango. Both men worked in the fields as pickers as children, Gonzales picking sugar beets, Acosta peaches; this, they did in addition to attending grammar school and doing quite well.

Both were respected athletes; Gonzales, a Boxer, who invariably turned professional (65-9-1) and was Ring magazine’s third-best featherweight in the world from 1947 to 1952, while Acosta was a high-school football star. Both were highly active in the early civil-rights movement; with Gonzales acting as coordinator of the Viva Kennedy campaign in Colorado, while Acosta worked in the campaign of Willie Brown in San Francisco and took part of the Mario Salvo Berkeley Student Protests at Sproul Hall in ’65.

Both men continually sought to foment social change, Gonzales through politics, running for Denver City Council in 1955, as community representative for the Five Points District, the Colorado Legislature in 1960, Colorado State Senator in 1964, and lastly, as Mayor of Denver in 1967 — though he lost every political race, he had more success as a grassroots organizer, where, among his accomplishments, he was seminal to the founding of the Crusade for Justice, and at the First National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference, his Spiritual Plan of Aztlán was adopted as the primary basis for the burgeoning Chicano Movement. Meanwhile, Acosta attended Law school at San Francisco State, passing the bar in 1966 and immediately went to work for Legal Aid in Oakland. However, this early foray into the harsh machinations of public defense only lasted a year, thereafter Acosta took a long alcohol and drug-fueled hiatus, before eventually returning to the law, primarily as legal defense for the Chicano Movement.

The lack of any sort of national cohesion in the early Chicano movement may have been the reason Gonzales and Acosta had not met until May 5th of 1970 at a rally at the UCLA Student Union, but after that meeting, their paths would be connected through the aforementioned Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 1971, and its aftermath.

It is unclear whether, or not Gonzales was aware of Acosta, however, we know that Acosta had been made aware of Gonzales, first through Thompson in the summer of 1967, near the end of their initial drug-fueled foray. Acosta writes in Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo:

“The Greyhound wouldn’t be pulling out for Denver for an hour, so we went into an Okie beer-bar and had our last Budweiser. Hank Snow was singing “Your Cheating Heart” when King said, What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know. Go to Denver first. Then to El Paso. I haven’t been there since I was five.”

“You ever herd of a guy named Corky Gonzales?”

“Nope. Who’s he?”

“Some kind of Mexican leader. I read he got busted with a bunch of Chicanos during some demonstration in Denver.”

“What are the Mexicans protesting?” I asked, not really concerned about the answer. The beer was flat now. The sting from the weekend of drugs was winding down.

“How should I know? Something about schools…you’re the Mexican, not me.”

“Well…all I got to protest about is my present physical condition.””

(pg. 179, Autobiography of A Brown Buffalo, Oscar Zeta Acosta, 1972. Straight Arrow Books, San Francisco. First Vintage Books Edition, July 1989.)

Roughly a year later, after some hard soul-searching, including a brief, brutal stint in a Mexican jail —an event which temporarily crushed his spirit —a penniless Acosta calls his brother Bob to hit him up for a loan in the early part of 1968 to travel to Guatemala and write about a revolution which was brewing there. Fortunately for Oscar, as detailed in the following excerpt from his Autobiography, his brother wisely pointed him in another direction:

“Jesus, Oscar. You’re getting carried away,” Bob says. “You know what? You’re beginning to sound just like dad.”

He tells me he is broke. Busted just like me. He can’t finance my excursion with Scott into Guatemala. He’s never even heard of a revolution down there. “And besides, even if you didn’t get your ass shot off, who would you sell your story to? Who’s your publisher?”

“I’m not worried about that. I just want to write. Anyway, I know this guy in Alpine. He’s a writer. He’ll put me on to a connection once I get a story.”

“Yeh, but shit, man…settle down. Just…look, if you want to write about revolutions…have you ever heard of Brown Power?”

“You mean the Negroes?”

“No, the Chicanos down in East L.A. I read a little paper called La Raza.”

“No. I’ve never heard of any of that. Why?”

“I read that they’re going to start a riot. Some group called the Brown Berets or something are going to have a school strike…I don’t really know anything about it. But it sounds… more practical. Why not go down there and write about that revolution, sell the story and then go to Guatemala?”

(ibid. p. 196)

That was the conversation which forever changed Oscar Acosta’s life, and was the impetus to connecting him onto Gonzales’ path. Acosta also writes in his Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo that it was that specific conversation with his brother which indelibly changed his outlook, as attested to by the following passage in his book:

“The bomb explodes in my head. Flashes of lightning. Stars in my eyes. I see it all before me. That is exactly what the gods have in store for me. Of course, why didn’t I think of it first?

An undercover agent for the good guys. The perfect front. Get a straight job. Work for the man as a cover. Hell, they’d never expose me. I am too tricky. I can make any kind of face you ask. After all, I’ve been a football man, a drunk, a preacher, a mathematician, a musician, a lawyer…and a brown buffalo.

Ladies and gentleman…my name is Oscar Acosta. My father is an Indian from the mountains of Durango. Although I cannot speak his language…you see, Spanish is the language of our conquerors. English is the language of our conquerors…No one ever asked me or my brother if we wanted to be American citizens. We are all citizens by default. They stole our land and made us half-slaves. They destroyed our gods and made us bow down to a dead man who’s been strung up for 2000 years…Now what we need is, first to give ourselves a new name. We need a new identity. A name and a language all our own…So I propose that we call ourselves …what’s this, you don’t want me to attack our religion? Well, all right…I propose we call ourselves the Brown Buffalo people…No, it’s not an Indian name, for Christ sake…don’t you get it? The buffalo, see? Yes, the animal that everyone slaughtered. Sure, both the cowboys and the Indians are out to get him…and because we do have roots in our Mexican past, our Aztec ancestry, that’s where we get the brown from…

Once in every century there comes a man who is chosen to speak for his people. Moses, Mao and Martin are examples. Who’s to say I am not such a man? In this day and age the man for all seasons needs many voices. Perhaps that is why the gods have sent me into Riverbank, Panama, San Francisco, Alpine (Aspen) and Juarez. Perhaps that is why I’ve been taught so many trades. Who will deny that I am unique?

For months, for years, no, all my life I sought to find out who I am. Why do you think I became a Baptist? Why did I try to force myself into the Riverbank swimming pool? And did I become a lawyer just to prove to the publishers I could do something worthwhile?

Any idiot that sees only the obvious is blind. For God sake, I have never seen and I have never felt inferior to any man or beast. My single mistake has been to seek an identity with any one person or nation or with any part of history…What I see now, on this rainy day of January, 1968, what is clear to me after this sojourn is that I am neither a Mexican nor an American. I am neither Catholic, nor a Protestant. I am a Chicano by ancestry and a Brown Buffalo by choice. Is that so hard for you to understand? Or is it that you choose not to understand for fear that I’ll get even with you? Do you fear the herds who were slaughtered, butchered and cut up to make life a bit more pleasant for you? Even though you would have survived without eating our flesh, using our skins to keep you warm and racking our heads on your living room walls as trophies, still we mean you no harm. We are not a vengeful people. Like my old man used to say, an Indian forgives, but he never forgets…that, ladies and gentleman, is all I meant to say. That unless we band together, we brown buffaloes will become extinct. And I do not want to live in a world without brown buffaloes.”

(ibid. p. 199)

It wasn’t long after that grey and rainy day in Los Angeles of January, 1968, that the neophyte Chicano activist and the veteran Chicano leader; respectively Acosta and Gonzales, would come together in a meaningful way. Albeit, there were vast differences in who they were as individuals: Acosta, more a dreamer and soul-searcher; a true product of the radical Sixties who, as we know through Thompson’s work, as well as his own, would frequently experiment with drugs in attempt to glean a sense of self-discovery. Gonzales, on the other hand, was more-straight-forward, athletic, and civic-minded, only partaking of alcohol occasionally. And yet, although their respective Dionysian and Apollonian natures may have seemed incompatible, together they blended yin with yang in a deft balance that would serve their community well.

The glue which inevitably bound the two would be the Brown Berets; a force for mobilizing the Chicano youth of the 60’s and early 70’s, born from the 1966 Annual Chicano Student Conference in Los Angeles. In the months after that conference, some of the attendees continued to meet, and in late 1966 created the Young Citizens for Community Action. In 1967 several of those members were educated in social action by Reverand John B. Luce at the Church of the Epiphany in Lincoln Heights, through the community service organization, thereafter changing the name of their organization to Young Chicanos for Community Action or YCCA. With the help of Luce, they obtained a grant which enabled them to open La Piranha coffeehouse in an abandoned warehouse on Olympic Boulevard and began hosting speakers such as Stokely Carmichael, Gonzales and Reies Tijerina — the fiery New Mexican revolutionary who shot up the Courthouse in his tiny hamlet of Tierra Amarilla, just northwest of Taos, New Mexico, in protest of land grant disputes going back to the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe. In September 1967, the group began meeting with Sal Castro, a teacher at Lincoln high School regarding issues surrounding public education. About this time, YCCA took a page out of the Black Panther’s book, and assumed a paramilitary style, donning their trademark brown berets, changing their name and shifted their focus to localized social issues such as police brutality, absence of political representation and health care, and the lack of sound education. Choosing the motto of “To Serve, Observe, and Protect” they additionally sought to act as buffer between the Police and the community. The Berets enjoyed a healthy growth spurt initially, and by 1969 had chapters in twenty-eight cities ranging from Milwaukee, to Seattle, to El Paso, and throughout Southern California. Their East Los Angeles Free Clinic enhanced their visibility in the community and was one of its most forward-thinking programs. They were also a seminal force in the 1968 blowouts, or school walkouts; and this is the event that put Gonzales and Acosta on the same path, although, on that day, the two had no relationship. This was the event, however, that launched Acosta’s legal representation of the Chicano community.

Google Doodle in honor of Corky Gonzales

A rally at UCLA in 1970 would be the venue for Gonzales and Acosta’s first face-to-face meeting, where both were headlining speakers. Acosta had gone from being the soul-searching drifter looking for meaning in alcohol and pharmaceuticals, to a notorious firebrand attorney and speaker for the Chicano movement, having quickly propelled himself into an echelon of prominent radicals such as Angela Davis, who was also a speaker that day, as well as the influential Gonzales. Acosta’s account of that day in his autobiography clearly delineates his style and approach from Gonzales,’ marking their vast differences in who they were as men, and how each sought societal change. Acosta’s matter-of-fact approach was an eyebrow-raiser, even for the controversial Angela Davis, who, herself didn’t pull any punches that day in her speech to the assembled UCLA students, telling them:

“We are here to protest the slaughter of the students at Kent State…We are here to join hands to fight against the warmongers…We are here to tell Richard Nixon that he can’t continue to bomb and kill the poor yellow brothers and sisters in Vietnam, in Cambodia...or at Kent State!”

“Right on, sister!... Tell it like it is!”

“Now, what we’ve got to understand, what we’ve got to see, is that the war in Vietnam, just like the war at Kent State, both are products of the system in this country…It isn’t just Nixon or Reagan or Yorty of Chief Davis. It’s the political system, the capitalist system, the racist institutions that are tearing this country to shreds…We have got to make it clear to those men in the White House that we won’t stand for it anymore!”

“We have got to organize ourselves…We must join together, black and white, students and old people, we must register to vote, we must get the people to the polls, we must get these pigs out of their positions of power! We must understand, we must be aware of their intentions. Nixon and Kissinger, Reagan and Agnew, these pigs have got to go!...”

The Black Beauty is soon escorted off the stage by three black dudes with sunglasses. They look around as they walk her to the rear of the stage.”

(The Revolt of the Cockroach People, p. 176)

The host of the rally, a red-bearded intellectual Acosta writes about disdainfully, due to his overt hip manner and flower-child-laden speak then introduces Corky Gonzales:

“And now…I’d like to introduce a man from out of state. Brother Corky Gonzales!”

The short dark Chicano comes on stage in a red shirt and black pants. His jet-black hair is cut short. He has white sharks teeth and the broad shoulders of an ex-boxer.

…Now I am as angered as you over the deaths of the four students …But where is Kent State? In Ohio…Let me tell you something. We teach our people in The Crusade For Justice that’s based on Denver, we teach our people to become involved in the local issues…We are just as much against the war as anyone. In fact, we have greater reasons for hating this war. Our people, the Chicanos, are being killed at twice our rate in the population. Chicano, blacks and poor whites, they are the ones that die. They are the ones that are sent to the front lines…Of course we are against the war…But we’ve got to take care of business at home first…

“Now I’m told that you had a mini-riot on the campus yesterday…My friends from this area have told me that the pigs busted some heads here twenty-four hours ago…They tell me that the Chicano students were holding a Cinco de Mayo celebration at Campbell Hall and that the pigs came in and busted some heads. Young boys and girls were clubbed down to the ground right here…”

“Let’s hear it for the Chicanos!”

“Viva La Raza!” Thin applause.

“So I would only add that you should get involved with the struggles in your own back yard…not just on the campus, but in the barrios, in the ghettos, wherever you find the forces of reaction working against the people, you must join in…You must not wait until an event becomes headlines, you must join with us now…Which reminds me…I understand the next speaker is a candidate for office in the coming election. They tell me that Zeta is running for Sheriff…He is running under the banner of our new political party, La Raza Unida…I would ask for your support of him. Thank you.”

(ibid, pgs.177-78)

Oscar Acosta in Los Angeles

Whereas Gonzales’ speech is matter-of-fact and to the point, appealing to the assembled student’s sense of inclusion in an attempt to rally them to the Chicano cause, Acosta, as you will see, takes a more challenging approach, exhibiting a tact and way of thinking beyond what most college-age radicals could imagine, his disdain for the “peace and love” movement and its inadequacies evident. Yet, the appreciation he and Gonzales feel for one another is already palpable, their appreciation for what the other provides for their cause, clear. Here, Acosta takes us back to that initial meeting:

“Corky emerges from behind the curtain. He throws his arms around my neck and gives me an abrazo.

“So you’re Zeta, eh?”

“Yeah man. About time we met.”

“Go on up and give these lame gringos hell. We’ll talk later.”

I stand at the mike staring down on the crowd of longhairs. They are sitting on the chairs, on the floors, standing around the edges waiting to hear from me.

“Let me first say that I’m not here for votes…Most of you probably don’t vote anyway…And I’m about as much a politician as Donald Duck…I have come to join in protest against the war. I have come to meet with you to add my words of sorrow for the kids shot down at Kent State yesterday…But more than that, I have come to ask you to join in support of the local issues. Just like Corky said…you know…death is not uncommon to us. We Chicanos have been beat up, shot up, kicked around, spat on and…fuck, they’ve taken everything we’ve had. …Death at the hands of the pigs is nothing new to us.”

“Preach, brother, preach.”

“Right on carnal!”

“But still I wonder…I must ask myself what the shouts of solidarity mean. You say to go right on, don’t you?”

“Amen!”

“You say that we’ve got to wipe out the pig, right?”

“Right on!”

“What we need is peace and love, right?”

“Hear, hear!”

“Give ‘em hell, brother!”

“Love and Peace, Peace and Love…with a little dope and a little rock on the side?”

“You’re talking, brother. Right on!”

“Hell yes, a little dope, a little love, a cheer here and there. Let’s march around the block, let’s go on up to the pigs at a skirmish line and give them hell…We’ll kill them with our buttons and our beads…We’ll slaughter them with our Rolling Stones albums, right?”

“Ah, come on man.” The crowd feels suckered.

“Sure, peace and love…Dope and rock…Solid, Jackson!”

“Hey, man? What are you driving at?”

“Let’s smother the creeps with flowers and posters, with acid and rock…Right on?”

“Hey, man cut out that divisive shit!”

“Screw you buster…I’m here to tell you that you’re fucked! You don’t know what you’re screaming! You don’t know what you’re asking for! Do you realize that when it comes down to it…and it will come down, believe me…When the fires start up, when the pigs come to take us all, what will you do? Will you hide behind your skin? Behind your school colors? Will you tell the arresting officers that you are with the rebels? Will you join up with the Chicanos or the blacks? Or will you run back to the homes of your fathers in Beverly Hills, in Westwood, in Canoga Park? Will you be with us when the going gets rough?”

“Hey man, Why don’t you wrap it up?” the redbeard calls to me. The crowd is getting ugly.

“Do you realize that you’ll have to shoot your mother? Do you realize that you might have to crack your uncle’s head apart? Will you be willing to do that? Do you think you can slaughter your own kind? I doubt it. I seriously doubt it.”

“Ah, fuck off, you creep.”

“Same to you pal… And the same to all of you out there who think that revolution is a game for a spring day. …Viva La Raza, motherfuckers!”

I walk away from the mike. Only a handful of Chicanos cheer me off. Corky and Louie meet me at the rear while the beard introduces the next speaker. We walk into a room behind the stage.

“You are too much, Buffalo.”

“Thanks man. You ain’t so bad yourself.”

I hear whispering in our room. It is Angela and her bodyguards, standing in a corner. A tall thin black woman comes up to them and opens her bag. Angela and her men look at us.

“It’s OK, baby” Corky says to her.

The three black men take pistols from under their coats and quickly stuff them in the woman’s bag. She turns and walks out.

Angela comes up to us. Corky hugs her. She turns to me and looks at me with those big lazy eyes.

“Brother…you are heavy.”

We touch and I give her my famous grin, the slight smirk of a malcriado out of his league.

“Sister, anytime you need a lawyer —or anything, you just call.”

“Thank you, Brown Buffalo,” the African Queen says.

We walk out into the night and hurry back to our turf.

Corky and Joe are talking about a massive demonstration against the war while I am drinking my wine alone.

They are planning to hold the biggest demonstration in the history of the Chicano Movement during the late summer.

(ibid, pgs. 177-78)

Perhaps it was the time Acosta spent in the midst of the “flower power” movement, frying on acid and ingesting whatever drug came his way, in a time and place where self-discovery and hedonism were inseparable, then seeing that approach getting nowhere which compelled him to give his fiery, matter-of-fact speech that day. Or, as he writes in Revolt of the Cockroach People, “the mad cross-country scampering with Stonewall (Thompson) and his crazy hippie friends, looking for the right questions and answers in a life of dope and easy living.” It was this restless meandering, of going paseando, which is the Aztlán version of the Australian walkabout, wherein one embarks on a long journey — not only to discover new lands, but to discover oneself — which afforded Acosta his unique perspective that day at UCLA and gave him the insight to stand up there, look down at the assembled masses, and see nothing but a tired re-hashing of a scene he’d witnessed countless times before. The fact is, though, it was Acosta who had changed. His time in the gritty, rough-and-tumble reality of East LA had deepened his insight, ground the lens of his perspective into the diamond-hard vision he now saw the world through. The harsh reality of doing battle with the government, as shown by the tone of the backstage scene at the UCLA rally, wherein Angela Davis and her cohort clandestinely handle firearms, casting furtive glances around the room to identify undercover agents of the system, or dangerous zealots opposed to their viewpoint, speaks volumes to the paranoia that accompanied being a true agent for change in those days. Incarceration and death were not only anticipated, but expected among most; whether they be Chicano or Black.

Cesar Chavez & Corky Gonzales.

This reality is the connecting thread between Gonzales and Acosta: knowing that one must subsume their fear of jail or death for the greater cause, to serve an ideal not yet attained. However, while Acosta was doing his soul-searching; not yet at the point where he felt compelled to lay it all on the line for a particular cause, Gonzales was already engaged in this sort of effort, becoming, with Cesar Chavez, one of the icons of the Chicano movement. Despite this fact, Acosta downplays his early knowledge of Gonzales in both his novels, Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, and Revolt of the Cockroach People, where, during the period of either work, Gonzales was already somewhat popular on the grassroots level; organizing marches and garnering the energy of the movement into viable opportunities to further the Chicano cause. In fact, as early as 1967, an early version of his soon to be recognized epic poem, I am Joaquin appeared in the September 16th of that year’s issue of the grassroots East LA publication, La Raza, where his bio that accompanies the poem reads:

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez, President of the Crusade for Justice, a militant based in Denver, is currently in Albuquerque, N.M. at the request of Reies López Tijerina to assist the work of the Alianza Federal de Mercedes. Corky is also coordinator for Vietnam Summer.

Corky speaks freely about la raza, about “A national movement of Mexican and Spanish in the Southwest — a militant movement that is not afraid to be linked with the spirit of Zapata, nor shy from the need to change the system, to have a social revolution…” A movement from Rio Grande City to Texas to Denver, from Delano to Tierra Amarilla.” He also speaks of “Our Mexicans” and “their Mexicans” referring to vendidos. “Too often we have a militant leader this year; next year he has some minor job with the U.S. Government, dealing with Mexican or Latin American problems, and we never hear of him again. He’s become their Chicano. Not Chavez and not Tijerina…who put everything on the line for the people, even life and family.”

Corky advises Chicanos to refuse to go to Vietnam as cannon fodder against “a beautiful people with whom we have no quarrel.” The fight for freedom, …land, …culture and language isn’t in Vietnam; it is here in the Southwest. If you must shed your blood it’s better that it be shed in Tierra Amarilla fighting for what is yours.”

Given the exposure Gonzales was experiencing, particularly from a seminal publication such as La Raza, it struck one as odd that Acosta hadn’t sought to align with him from the outset. However, Acosta wasn’t the only one engaged in the revolution with a myopic view, as is evident from the following quote from his Revolt of the Cockroach People, wherein Acosta relays the story of how his close-knit group of Chicano Militants and vatos locos sought out a private meeting with Gonzales in the wake of the Moratorium riots, even after Gonzales had been acknowledged as a prominent organizer of the event, even arrested on a weapon charge that fateful day:

They ask me about Corky: how does he stand? Can they trust him? Aside from Cesar Chavez, he has the biggest reputation as the toughest Chicano in America. But he is an outsider, from Denver. Can they all work together? I tell them not to worry, that Corky is a man to be trusted.

But they still want to meet with him and talk with him personally. Since only Corky is not out on bail, they haven’t been able to see him. After I talk with them, they still want to see him. They want to check out if they can trust him. Which means they don’t trust me anymore. They just need me. I promise to arrange a meeting in a few days and get to work on the cases. Then we split.

(ibid, p.207)

A short time after that passage, Acosta sets up the meeting with Gonzales in his downtown LA apartment he shares with some of the crew. Frankly writing about how it went, he tells us:

Corky has on his usual red shirt and black pants. He comes in cagey like the top professional boxer he used to be. He knows the men are here to run him through some tough questions. He knows he is still considered an outsider to the vatos on the streets. Tonight, here in LA, he knows the mistrust one Chicano has for another. He understands the fear in the room toward a leader from another barrio, suspicion of a strange leader because…because Santa Anna sold us out to the gringos…because Juarez did nothing about it…because Montezuma was a fag and a mystic who had the fear of the Lord for Cortez or for Malinche…because anybody who has so little is afraid to lose what he just barely has got, saith the Lord.

“OK, you guys,” I say,” here’s Corky. You got some questions?”

“Hey, man…Don’t I get a chance first?” Corky says, flashing his big white teeth.

“Yeah, come on,” says Gilbert. “Sit down, ese, and have a joint.”

“I don’t smoke those little numbers,” Corky says.

“He’s a boozer,” I say.

“The jefe just likes to drink Old Fitz,” Louie says.

“I’m particular,” Corky jokes. The men are still hard against him.

I invited you cause the dudes want to ask you some questions…I’ve been telling them about you. I’ve told them I’m going to defend you. But they keep bugging me on whether you’re heavy or not…So, fuck it, you answer their questions…OK?”

“Sure, Big Bear. Don’t get excited…OK, but first let me say this…Whatever you guys decide tonight is OK with us…We recognize we are on your turf…We will support whatever you guys decide.”

“Hey, ese,” Gilbert says. “How come you guys still want to march and stuff like that?”

“Who?” I don’t want to march, man. I’m as tired of that shit as you. But if the people want to have a demonstration…It’s what they want that counts… You think I got the twenty-five thousand out there?”

“What Gilbert wants to know…” Pelon says.

“Hey, puto, I can talk for myself!” Gilbert shouts back.

But Pelon keeps on. “He just wants to know like we do, man. If the going gets heavy, are you guys into it?”

There is silence. We hear the buzz of the lights in the fish tank, the bubbles fizzing to the surface.

“Listen…We’ve been t this game for almost ten years. We don’t tell the kids to pick up the guns. We will not tell them to pick it up. But we do believe in self-defense…and if it’s necessary…we do what is necessary. That’s all.”

“But you guys don’t want to throw firebombs?”

“No. We don’t. It doesn’t serve our purposes now.”

“Then why don’t you tell the dudes who are doing it to stop doing it?”

“Are you kidding?”…Man, if any Chicano comes and tells me what to do, what is the first thing I think? Que es Marrano, right? We don’t believe in telling others what to do. If you guys are throwing bombs, it must be because you feel that its necessary to do so in order to accomplish your objectives…We don’t…Not at this time.”

“Do you support the Chicano Militants?”

He laughs. “Hey, ese, don’t you read the papers?... I’m supposed to be the leader of you guys…Of course I support you.”

“How about the Chicano Liberation Front?”

“Who is that?” Corky says.

“Hey, aint’choo heard about…a kid with a beanie begins to ask.

Gilbert slaps him with a brown beret, laughing, “Don’t be so tapado, ese…This vato is cool.”

(ibid, pgs. 211-13)

The account of the meeting between Acosta’s crew and Gonzales is telling in several regards. First, it speaks to the sense of mistrust between geographical regions within the Chicano movement. Secondly, it shows how the pressure of being at war for an extended period of time with the powers that be wears down one’s nerves; and, thirdly, it shows how the movement was doomed to failure, due to a lack of cohesion and a coming to terms of clearly-defined goals and singular unifying principles, particularly at that late juncture. Of course, it’s easy to make such declarative statements in hindsight. Yet, the writing was on the wall; the fire of the Seventies rebellion was to be doused by the oncoming wave of the “me” decade; a time of increased focus on acquisition and selfish individualism, which encouraged all to materially advance themselves at the sake of the collective.

But before that, the fire of the revolution was to be tempered in the courtrooms of the land. The sweeping changes intended; the mass protests and fitful violence to be judged and codified before becoming policy. This is what it all boiled down to: the gears of change were slowed by these mechanisms. What came out the other end became what was to be. The radicals would be incarcerated, disenfranchised, or co-opted. Politics would play its part in the process. At the crux of this maelstrom of change was the Brown Buffalo. He would stomp on the terra of the judicial land in a way no one had previously done. However, this was not without consequence. The process would push him to the limit of right and wrong; force him to compromise his own sanity, and forever cast him in a role which would inevitably be his undoing.

Home Court Advantage? Justice… Aztlán Style

Sal Castro. Courtesy La Times, Getty Images

As a result of our decision in this writ proceeding and the passage of time, several of the petitioners who, according to the evidence presented to the grand jury, clearly committed or aided and abetted in the commission of several misdemeanors, may never be tried for those crimes. We share the view of anyone who thinks that this is a most undesirable result. We stress, however, at the outset, that with one minor exception [9 Cal. App. 3d 678] noted herein, the authorities did not choose to charge the misdemeanors. This opinion therefore cannot and a fortiori does not deal with crimes which, at the time of their public commission, generated considerable notoriety.